Introduction to Water Source Heat Pump Systems Part 3: Basic Operation

/By Chad Edmondson

How does a water source heat pump (WSHP) work?

WSHPs operate similarly to traditional air source heat pumps (ASHPs) in that they transfer heat rather than creating it from a combustible fuel. Both incorporate a refrigeration cycle to facilitate heat transfer and both include a valve to reverse the cycle, depending on whether the unit is in heating or cooling mode. The primary distinction between WSHPs and ASHPs is that WSHPs absorb and extract heat from a water loop while ASHPs absorb and extract heat from the outdoor air.

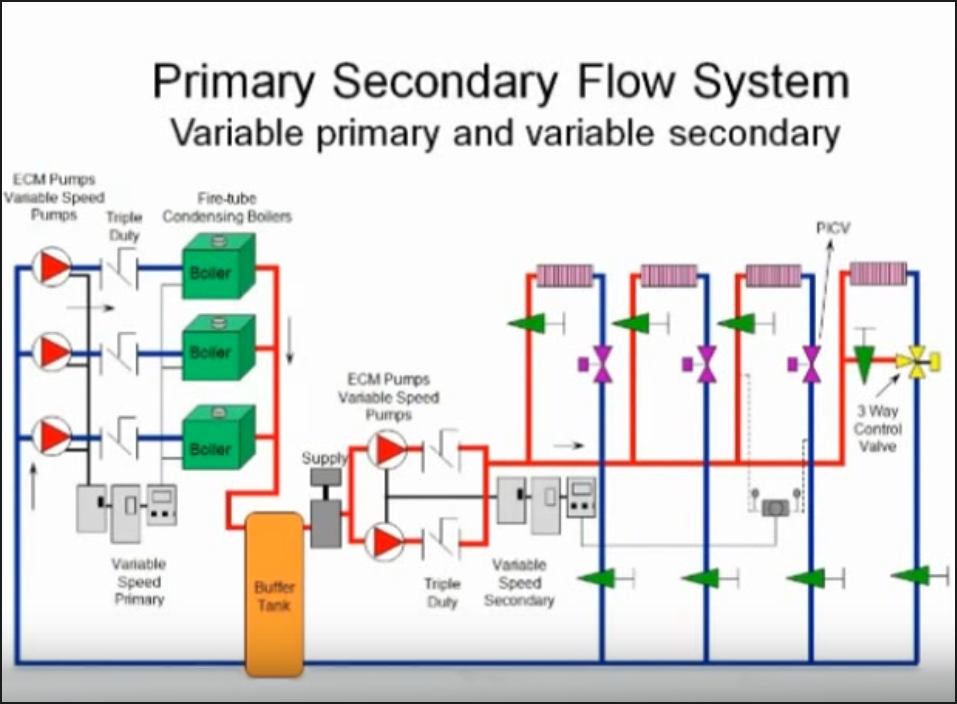

Typically in commercial applications, multiple WSHPs are connected to a common water loop which is maintained within an operating temperature range of 60°F to 90°F. When more zones need heating than cooling, the loop temperature drops (approaching 60°F) and the boiler may be activated to make up the heat deficit, thus returning the loop to its operating range. When more zones need cooling than heating, the loop temperature rises (approaching 90°F) and the cooling tower may be activated to reject the surplus heat.

Because buildings with multiple zones encounter peak heating and cooling demands at different times during the day, individual heat pumps usually have capacity to spare. So boiler or chiller operation may only be necessary during peak heating and cooling seasons.

WSHP Refrigeration Cycle

The only “complicated” part of a WSHP is the refrigeration cycle, but of course the same could be said of any heating or cooling equipment that relies on refrigerant, including your refrigerator.

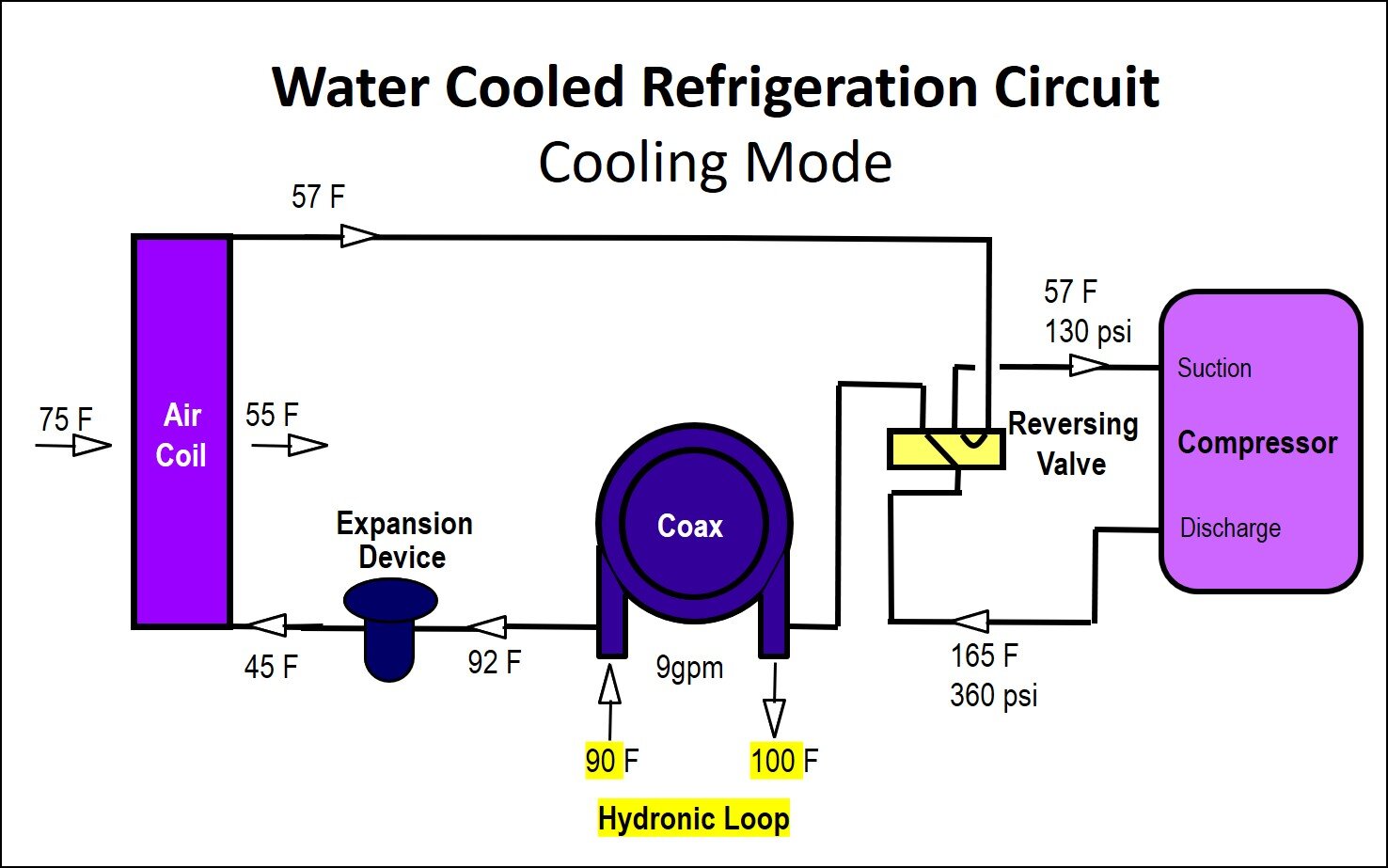

WSHPs include two heat exchangers, a refrigerant-to-water heat exchanger and a refrigerant-to-air heat exchanger. The water side of the refrigerant-to-water heat exchanger is fed from the central hydronic loop. In cooling mode this heat exchanger acts as the condenser while the refrigerant-to-air heat exchanger acts as an evaporator.

When the WSHP is operating in cooling mode, heat is extracted from the hot return (building) air in the refrigerant-to-air coil through evaporation of the refrigerant. Meanwhile, hot gas from the compressor discharger is directed into the refrigerant-to-water heat exchanger where the hot gas condenses into liquid, giving up its heat to the colder loop water as it passes through the heat exchanger. Liquid refrigerant then passes through a metering device situated between the heat exchanger and the refrigerant-to-air heat exchanger (coil) where it evaporates, resulting in a drop in temperature on the air side. This cooler air is pushed into the space by a blower.

In heating mode, the process is simply reversed by way of a reversing valve that sits between the compressor and the refrigerant-to-water heat exchanger.

Water Loop Lightens the Load on the WSHP

Many WSHP systems provide simultaneous heating and cooling throughout most of the year. This is when a WSHP is operating at its most efficient, recovering and redistributing heating and cooling without the help of a chiller or boiler.

This is what makes WSHPs so efficient. Since the “give and take” of Btus between the building zones and the water loop makes it easy to keep the loop temperature between 60°F and 90°F with little or no help from the boiler or chiller, it is incredibly efficient. After all, if it is 20°F outside, it is a lot easier to heat a building by extracting Btus from 70°F water than from 20°F air. That’s less work (refrigeration cycling) that the heat pump has to do!